Interviewer: Rain, Program Host

Interviewee: Salai Thang Loon, Major

Rain: Hello, thank you for taking the time to join us on *The Kaladan Post*’s Youth and Women’s Affairs Program. First of all, could you please introduce yourself, including your name, the organization you are currently working with, and your role or position?

Salai Thang Loon: Hello, my name is Salai Thang Loon. I am currently serving as a Major in the Chin National Front (CNF) and Chin National Army (CNA), a revolutionary armed organization.

Rain: Alright. So, before the 2021 coup, what were you involved in, and what experiences or perspectives led you to participate in the current revolution from your standpoint?

Salai Thang Loon: Before the 2021 coup, to summarize my involvement, I entered university in 2010. In 2013, I served as the General Secretary of the Chin Literature and Culture Committee. Then, from 2015 to 2018, I was the General Secretary of the All Myanmar Chin Students’ Union, which was formed by Chin students from various universities across the country. During that time, in October 2015, when the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) was signed, the Chin National Front was one of the armed groups that signed the agreement. From that period, I began to understand the importance of national consciousness and the role of citizens, regardless of age, in the struggle for national liberation, democracy, human rights, and political rights. Through studying these issues, I gained clarity and started engaging with the Chin National Front in 2016. When the NLD government came to power, I was involved as the sole Chin youth representative in the drafting committee for the National Youth Policy. Additionally, I played a leading role in forming the Mindat University Students’ Organization. Later, in my hometown of Kanpetlet, I helped establish the Kanpetlet University Fellowship and served as its General Secretary. In brief, my activities revolved around ethnic and regional initiatives.

Rain: Alright. After the coup, what political or military activities have you been involved in, and what were the main challenges you faced during these activities?

Salai Thang Loon: The primary motivation wasn’t about being instructed by anyone. The concept of nationalism is about personal conviction and sacrifice. It’s about giving everything, even your life, if necessary, for national liberation and the armed struggle. Political issues should ideally be resolved politically, but military solutions have also been necessary due to the prolonged civil war in our country. For the Chin people, I strongly believed that a robust armed organization was essential, driven by a deep sense of nationalism. After completing university, I became actively involved with the CNF starting in 2016. I’ve done my best in both military and political spheres, but there are areas where we’ve succeeded and others where we still fall short. The main driving force behind my involvement in the national struggle was the realization that we must contribute to our people’s liberation. If we don’t act, who will? Before the 2021 coup, from 2017 to 2019, I traveled across states, townships, and villages to mobilize, recruit, and encourage young people to join the cause as fighters or trainees. At that time, the political climate was relatively stable, and many didn’t support the armed struggle. However, by 2019, four years after the NCA, it became clear that political negotiations were stalling. Speeches by Min Aung Hlaing and Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, along with debates about secession or a unified nation, made me reflect on our efforts. Compared to other armed groups with greater strength, our organization was small, with only a few hundred members. Still, I firmly believed that if we didn’t act for our people’s liberation then, when would we? With this conviction, I fully committed myself. I had a sense that a coup might happen, not as a prophecy but based on political awareness. In some villages, I warned that a coup was likely, especially given the escalating conflicts in neighboring Rakhine State. I emphasized the need to prepare militarily, as we couldn’t trust the military to refrain from seizing power again. In 2019, I underwent basic military training, transitioning from a regular fighter to officer training in early 2020. By connecting with many young people, we built momentum. After the coup, our activities continued seamlessly. I spent nearly three years in Kachin State. Upon returning, I rested for only two weeks before heading to the frontlines. One of the most notable operations was the Simon Operation, where we destroyed tanks and military convoys for the first time—a widely recognized achievement. I personally led three camp seizures, including the Rezua camp, where I breached the perimeter and gave orders, and the Bungzung camp, where I again led the charge. Seeing comrades fall in battle was heartbreaking. When capturing prisoners of war, emotions ran high, and there were moments when we wanted to harm them. However, we adhered to the Geneva Conventions and military ethics taught in officer training. Despite the urge to act out, we restrained ourselves, though some minor physical outbursts occurred. In summary, my military experiences include these operations, while politically, as soldiers, we focus less on political discussions. The Myanmar military’s involvement in politics has led to the country’s ruin, so we prioritize action over political rhetoric, though we continue to study and analyze political matters. That’s the overview.

Rain: Alright. So, the main goal of our revolution is to overthrow the military dictatorship, correct? However, as the revolution has prolonged, we’ve been encountering issues of disagreement among the revolutionary forces. To what extent do you think these disagreements could impact the revolution? And how do you believe these issues can be best resolved?

Salai Thang Loon: Since the 2021 coup, in our ethnic regions, there have been numerous organizations. If we look at the mainland, the number of armed groups—battalions and forces—has reached thousands, even tens of thousands. Recently, there’s been some consolidation, but there’s also been significant fragmentation. Our number one priority, starting with the civil servants who joined the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM), was to sacrifice everything to topple the military dictatorship. They raised three fingers and joined the CDM. Not only that, but through various means, including armed struggle, we’ve been trying to dismantle the junta’s unjust seizure of power for over four years now. During these four years, we’ve faced disunity and fragmentation. This is something we must encounter. If you look at civil wars in other countries, these dynamics are quite common. What’s our goal? What’s our destination? We need to keep that in our hearts and minds, unwavering. The junta thrives on the disarray and fragmentation of the revolutionary groups and individuals fighting against it. That’s why they refuse to relinquish power. Since independence in 1948 up to 2025, the Myanmar military—whether called the Myanmar Army or the Burmese Army—has been the root cause of the devastating civil war. The junta we’re fighting against must be destroyed. Over the decades, there have been four coups, and they’ve learned many lessons. They exploit opportunities, entice, negotiate, and reintegrate revolutionary groups, gradually ensuring the perpetuation of their authoritarian rule. We need to understand this historical lesson. In many countries, a civil war lasting 50 years requires an equal amount of time to heal. So, we’re talking about another 20 years of endurance. During this time, whether by city or region, we must never lose sight of who we’re fighting against and what our ultimate goal is. If we understand this, no matter the method—whether it’s cooking rice or whatever—we act based on our convictions, and that’s what makes it worthwhile. Mutual respect, recognition, and dialogue between individuals and groups are incredibly important. If we continue with this fragmentation, the junta will exploit it, just as they have in past coups, saying, “They can’t even get along among themselves,” which strengthens their position. In terms of international relations and diplomacy, the junta’s illegal seizure of power means they still hold illegitimate authority. For us, the National Unity Government (NUG), operating as a parallel government, even gaining entry into international spaces is not easy. I’m not saying this to discourage anyone or make us lose sight of our goals. We need to weigh the strength of our forces against the junta’s might and stay united, respectful, and solution-oriented through dialogue and meetings.

Rain: Understood. How do you assess the perspectives of Myanmar’s neighboring countries, such as China, Thailand, and India, regarding our revolution? How might their stances affect the success of the revolution?

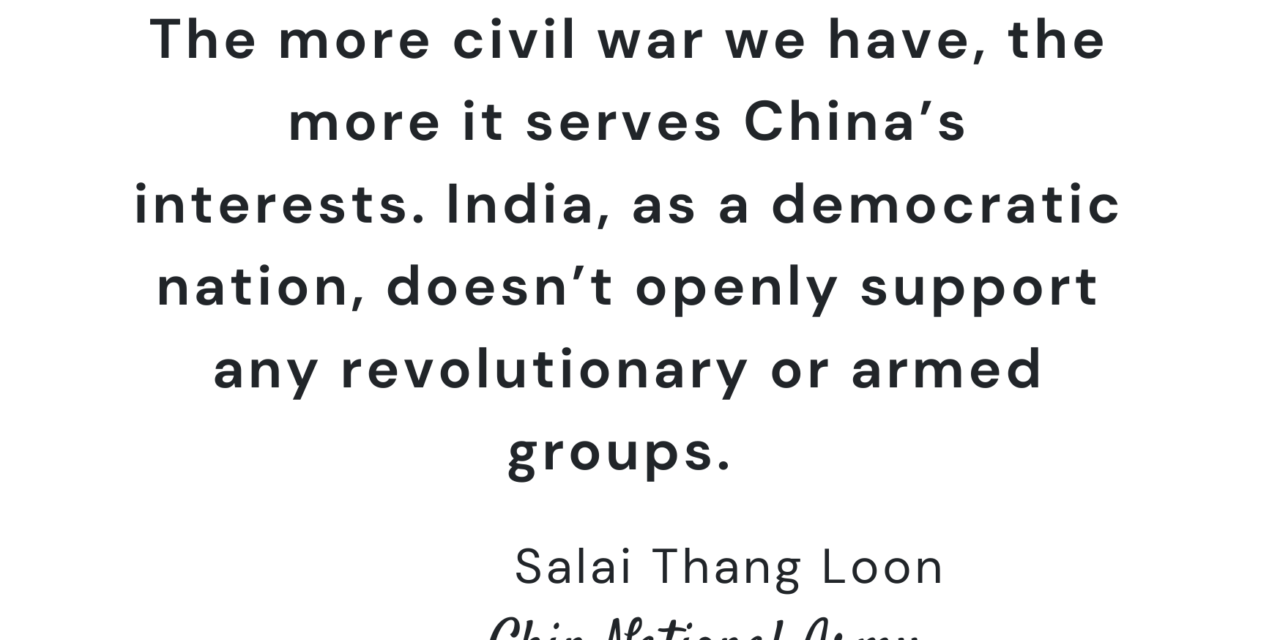

Salai Thang Loon: The three countries most closely connected to us—China, India, and Thailand—have significant impacts on Myanmar, both positive and negative, when analyzed from military, political, legitimacy, and diplomatic perspectives. The more civil war and conflict we have in Myanmar, the more it benefits China’s interests. Why? Because if Myanmar had a vibrant, people-centered government capable of competing internationally, China would lose many of its opportunities and advantages. That’s why some say China treats Myanmar like its own territory. China’s interference in Myanmar’s politics and revolution is something any observer of the political landscape would understand. The more civil war we have, the more it serves China’s interests. India, as a democratic nation, doesn’t openly support any revolutionary or armed groups. Thailand, on the other hand, excels as an arms broker. When it comes to the impact of these three neighbors, India’s competition with China creates a complex dynamic. They may seem to support revolutionary groups indirectly but are cautious due to their Northeast Policy and rivalry with China. In short, the more conflict we have in Myanmar, the more these countries benefit. That’s how I’d briefly assess their influence on Myanmar’s regional politics.

Rain: Alright. As a young person yourself, how do you view the leadership role of youth in this revolution? What are the main challenges and difficulties young people face when taking on leadership roles in this context?

Salai Thang Loon: As a young Chin revolutionary, the situation in the revolution since the 2021 coup has changed dramatically from the early days to now. We are young and middle-aged, and while there are many good older Chin leaders, many of them hold conservative views. Some young and middle-aged individuals have also inherited what we might call the negative legacy of the older generation, and we’ve been facing and feeling these challenges more recently. As a young person, when looking at the revolutionary organizations like the Chinland Council (CC) and the Chin Brotherhood, both have young people involved. These organizations are a mix of young and older individuals. Lately, many people—both within Myanmar and abroad—seem to think they are the most important, that the revolution cannot succeed without them. This mindset, where everyone wants to be significant, is a major issue. When looking at the leadership roles across generations—youth, middle-aged, and older people—everyone has a spirit of sacrifice. In Kachin, where I spent nearly three years, the KIA would say, “Whether this revolution succeeds or not, whether we achieve independence or not, it can happen without you, but it’s better if you’re involved.” So, the issue is that many people, both domestically and internationally, want to be seen as crucial, which creates problems with participation and interference. In terms of leadership on the ground, among my peers, there are many young people involved in the revolution. In Chin revolutionary groups, about 80% of those carrying arms are youth aged around 20 to 35. The remaining 20% are older individuals. However, we lack robust leadership among the youth. No one dares to fully entrust leadership to others, and I’m not targeting any specific person or organization here—it’s just my observation and experience. Among young and middle-aged people, there’s a lack of accountability and responsibility in leadership roles. There’s also a shortage of youth capable of making decisive decisions. For us Chins, we’re stuck in a transitional phase between older and younger generations. As a young revolutionary, I feel like we’re in a limbo—neither moving forward nor stepping back, like being stuck on a hill.

Rain: Understood. We’ve also seen significant participation from women in this revolution. How do you assess their roles in military, political, and administrative aspects? And what suggestions do you have to strengthen their participation?

Salai Thang Loon: Gender equality is a social concept, but in military and political spheres, it’s often absent or unequal. In this revolution, if we look at countries fighting for independence in civil wars, women’s roles are incredibly effective. For example, in the Jewish liberation movement, a woman started fundraising efforts, which helped Israel reclaim its land step by step and achieve independence. Similarly, in countries like Indonesia, Vietnam, or the Philippines—our neighbors with histories of civil war—women’s contributions have been immense. In Chin culture, I’m not sure if it’s deep-rooted tradition, but many women tend to feel inferior or lack confidence. Additionally, some men dismiss women, saying they can’t do this or that, or telling them to stay quiet. From my perspective, women’s participation in liberation, politics, and other areas is extremely important and effective. Women often show greater courage than men. Once they make a decision, they pursue their goals with remarkable determination. Moreover, women’s involvement brings unique perspectives, making it incredibly significant. Look at any country or organization—those with strong female participation and leadership thrive. Women’s involvement is a source of strength. For instance, at the frontline, when we’re injured or fighting, women’s contributions—from medical care to logistics—are unparalleled. Compared to men, women’s encouragement, their nurturing “motherly” spirit, is unmatched. I’ve experienced this many times: women in logistics, medical care, transportation, or cooking inspire us automatically. Seeing women participate with such enthusiasm makes us men feel that even if we die, we’d die fulfilled. I believe every fighter feels this. Take female comrades, for example—when they cook or deliver food, it’s incredibly motivating. Women’s prayers, fasting, and sending blessings are truly uplifting. The more women participate, the stronger our revolution and society become. I firmly believe that the greater their involvement, the closer we get to our revolutionary goals. Women need to have more courage and participate more. They are the ones who can guide and inspire men, offering correction, encouragement, and comfort. The sound of a woman’s encouragement alone boosts morale. The higher the percentage of women’s participation, the closer our revolution comes to success. From my experience, I want to emphasize just how critical women’s involvement is.

Rain: Alright. Looking beyond the revolution, what kind of future do you envision for Myanmar? How do you picture it? And to prevent the re-emergence of a military dictatorship in this future Myanmar, what foundational measures or policies do you think should be put in place?

Salai Thang Loon: To achieve the kind of country we want, the number one priority is to secure true independence. For that, a constitution is absolutely critical. A nation’s lifeblood is its constitution, which protects and safeguards all its citizens. Although our country gained independence in 1948, it has been a hollow independence, and even today, we lack true freedom. First, we need genuine independence. Second, we need a constitution that aligns with our country’s needs. Myanmar is a nation composed of diverse ethnic groups, so the constitution must guarantee self-determination for all ethnic groups. Currently, we don’t have that. If you look at the 1947 constitution or the 1974 constitution, they don’t provide this. The 2008 constitution is even worse. The unitary system and the constitutional provisions have been manipulated by the military, allowing them to seize power at any time. So, for the country we envision, we need: first, true independence; second, a constitution that guarantees the rights of all citizens and ensures that ethnic states and regions have their own self-determination and constitutions. The most critical issue in our country is that the military can easily stage a coup. We need a constitution that guarantees this cannot happen. The ongoing civil war in our country is fundamentally a political problem rooted in the constitution. Our ethnic groups’ demands for self-determination have not been met—not a single one. This is why the civil war persists. If we adopt a system with a proper constitution, we can achieve the country we desire.

Rain: Understood. Finally, what is the most significant lesson you’ve learned during this revolutionary period? And what message would you like to convey to the Myanmar people and the international community?

Salai Thang Loon: Across many countries, both domestically and internationally, we Chins are not a people who have historically chosen and elevated a single leader to govern us, unlike other ethnic groups like the Mon, Bamar, or Rakhine, who lived under monarchical systems. We’ve lived under a village-based, localized system, which makes unity incredibly important. This is a golden opportunity, a critical moment. Our neighbors, like what was once called Lushai, now Mizoram state, fought a 26-year revolution against their central government. Back then, they were also fragmented, with villages at odds with one another. There were betrayals and collaborators, but they eventually achieved the Mizoram Peace Accord with the central government. Similarly, we Chins have the opportunity to reach that point—we just haven’t gotten there yet. Right now, Chins living both in Myanmar and abroad, across various countries, need unity to rebuild and reconcile our nation. This is the best time for Chin nation-building, the right time with the right policies. We must strive and struggle without losing heart. We will likely face even tougher times ahead, so we must avoid making unforgivable mistakes. Every organization, leader, fighter, and citizen have a responsibility. Among the Chin community, some believe this revolution will fail, feeling demoralized, thinking they might have to return to the junta or revert to CDM in a compromised way. There’s significant disillusionment among the Chin public regarding this revolution. We cannot afford to lose heart or retreat. If we step back or give up, the armed revolution we started will face even worse consequences. What we’re facing now is just a taste of hardship. If worse conditions arise, we must endure and maintain faith in this revolution. My chosen path—armed revolution—is because political solutions alone cannot resolve this political crisis. It has reached a stage where military means are necessary. My choice is driven by a clear goal and purpose. This isn’t a futile endeavor or a waste of time, causing suffering or separation from families. I chose this path out of conviction. I urge Chins at home and abroad, across the international community, not to lose heart. We haven’t reached our goal yet, but we will get there someday. We cannot give up on this revolution. You may lose faith in some individuals, but not in the revolution as a whole. It’s a collective responsibility. We’re not playing a game or carrying arms for fun. We have a goal, a purpose, a destination. One day, we will/we are people who are responsible to establish a free and independent union/ One day, we will be a people who establish a liberated, independent union. We are a people blessed by God, given land to live on, and we must govern that land. We must not forget this, lose heart, or give up on this revolution. This is the message I want to send to all Chins worldwide.

Rain: Alright., that’s all for our discussion program. Thank you so much, Sir, for sharing your situation and insights

Note: This translated text represents our effort to help international observers of Myanmar affairs gain a more accurate understanding of the actual situation in Myanmar. If there are any shortcomings in the translation, we respectfully request that you consider the original Burmese meaning as the authoritative version.