“we need to work with neighbouring countries to balance mutual interests “

Program Host, RAIN: Greetings, sir. First of all, thank you so much for joining us on The Kaladan Post’s Youth and Women’s Affairs Program for this interview segment. We understand that you are not only a CDM (Civil Disobedience Movement) participant but also a poet. Could you please introduce yourself by telling us about your role before joining the CDM, which department you worked in, how you established yourself as a poet before the revolution, and what activities you are currently involved in?

Poet Har Shine: Yes, thank you. I am Har Shine, a poet. Previously, I worked as an Assistant Director in the Land Records Department under the Department of Agricultural Land Management and Statistics in Kalay Township. When the coup happened, as a poet and someone from Kalay—a place known for strong political and student movements—I naturally gravitated toward the revolution. We were already connected with literary circles, the All Burma Federation of Student Unions (ABFSU), and the Chin Literature and Culture Committee. These ties with student activists and political figures were longstanding.

As a poet, I lean toward leftist ideologies, so even before the coup, during the NLD and U Thein Sein governments, we were actively involved in challenging the 2008 Constitution and the aftermath of Cyclone Nargis. We consistently spoke out and participated in movements like the 2015 protests, both as civil servants and poets.

I believe this point is one of the main reasons among many for engaging in the CDM (Civil Disobedience Movement). Before I got involved in the CDM, as part of the literary community, we had been active in various ways. If I were to highlight a key aspect, it would be the establishment of a poetry award in the Chin Hills, something significant and meaningful. In Myanmar, there are awards like the National Literature Award, the Yoma Literature Award in Pyinmana, and the Irrawaddy Poetry Award in Kyaukse, among many others. However, from Chin State, not a single poetry award has been given yet, despite having the potential and capability to do so.

There are numerous Chin poets from the Chin Hills. However, they had not been able to establish a significant poetry award despite their efforts. The Chin poets worked together to create a poetry award called the “Tawngzalat Land Poetry Award” and successfully awarded it. Later, just before COVID, I collaborated with a poet from Paletwa, Teacher Mya Kabyar, to support the war-displaced people of Paletwa through poetry. As Chin poets, we felt a responsibility to assist in any way possible.

As brothers, we believed poetry could be a means of contribution. So, the Chin poets decided to compile a poetry anthology. Together, we successfully published a poetry book titled The Longing for Peace/ Nyeinchanyee Khaungyee, which included works from all Chin poets. This took place before the coup and remains a cherished moment in our literary journey. Reflecting on my own literary journey, in 2007, my poem Kunbong was published in Youth Magazine as my first printed work.

That was my first published work in 2007. I mention this because many people have been talking about it in various ways. Currently, I am actively participating as an executive member of the All Myanmar Youth Poets’ Association (BalaKata).

Program Host, RAIN: In 2021, during the coup, what personal beliefs, social pressures, or political circumstances primarily motivated your decision to join the CDM? What challenges did you face when implementing this decision, such as repression from the military junta, financial difficulties, or family concerns?

Poet Har Shine: “On behalf of the students of NYRDDC and NRDC, also known as Natala, I released a statement opposing and rejecting (the coup). After releasing the statement, from Batch 1 and 2 were insulting and attacking me. Many seniors even said they would slap me if they saw me on the street. As for why I actually joined the CDM, it was because of the 2008 Constitution. Regarding the 2008 Constitution, whether to amend or abolish it — even if it is amended, about 80 percent of it would need to be changed.”

If it wasn’t changed that much, then for us it would not be acceptable. That’s how I ended up in the revolution. The main difficulty was that during the protest period, when we were peacefully marching and demonstrating, they restricted us by shooting and blocking — so it shifted towards the path of armed revolution. In the early days of the CDM, the real suffering was that senior figures and teachers who thought politically became the main threat. They said things like, ‘The revolution will be over by tomorrow,’ or ‘The CDM staff only have to hold out for one week, then we’ll win.’ Those kinds of statements put enormous pressure on the civil servants who had joined the CDM.”

That’s how it was. Some didn’t support the revolution; they supported the military. But on this side, in terms of human rights and rights in general, most people sided with the majority. With beliefs like ‘Tomorrow it will be over,’ or ‘If you do CDM for one week, the revolution will be finished,’ or ‘After the revolution ends, we’ll be rewarded,’ many people joined the CDM. But since they didn’t join out of real conviction or strong determination, it caused a lot of suffering.

Another challenge was living in government housing in Kalay, near the Taungphilar Golf Course. After joining the CDM, it became unsafe as the military stationed troops there around the 10th day of the coup. The staff housing was completely under their control. Their officers, who were staying there, went as far as investigating which rooms, which apartments, which departments, and which civil servants had joined the CDM. For us, that made things even worse.

It’s like I’m kind of part of the strike committee, but not really, and sort of involved with the leadership committee, but not quite. The situation with the government employee housing is just as unclear—there’s this pressure to evict us CDM (Civil Disobedience Movement) employees, but also a sense that we don’t have to leave. Yet, if they say we must leave, the military is stationed at the entrance, ready to pounce. If I pack my bags and leave, it’s like announcing I’m part of the CDM, and they’ll just grab me.

So, I had to slip out of the employee housing quietly, with just a single piece of clothing, like a fugitive. My family and I left together, and not long after, I saw and heard that the first People’s Administration Team in Myanmar was formed in Mindat town. I thought, if that’s the case, I’d return to my hometown. The real strength lies in administrative work—office and staff roles, right? I figured I could help with that, so I left to contribute.

When I returned, since the Pa-Ah-Phah (the People’s Administration Team) group was made up of my own people. At first, I helped out from the outside. Later, I worked as an office team leader under Poet Soe Pyae’s office group. Then, when the internet lines were cut, we were left wondering what to do. So, we collaborated with Ko Yaw Man’s group at Ng’kawn Cha. One person would run to Khaophyu, copy and paste information into notes, type it up on the computer, and produce the Spring Newsletter. We sent out news—that was the early stage of my revolutionary journey.

Now, what we often face is people saying, “You CDM folks aren’t real revolutionaries. Real revolutionaries are those in the armed struggle, or at best, you’re second-tier revolutionaries. Or maybe you’re not revolutionaries at all.” They say only those carrying weapons are true revolutionaries. Facing those words and looks is deeply disheartening, especially amidst all the hardships.

Why? Because to reach the armed revolution, we had to go on strike. The strike included CDM employees, the CDM public—everyone’s efforts lifted the armed struggle onto its path. We carried it on our shoulders, but now we’re told, “You CDM people aren’t revolutionaries.” Those words and looks are tough to bear

Program Host, RAIN: Alright. So, the next thing I’d like to ask is, as a poet, have you written poems that reflect your emotions, experiences, and the fighting spirit of the people? Could you share the story behind a memorable poem you wrote, including its content and the reason you wrote it?

Poet Har Shein: During the revolutionary period, I mostly wrote revolutionary poems. From the day of the 2021 coup until around 2023, I think. Sentimental poems, love poems, or those about life’s sorrows and nostalgia—I didn’t write any of those. I was consumed with the drive to write only revolutionary poems. I even felt that if it wasn’t a revolutionary poem, I wouldn’t write at all.

In September 2021, for my birthday, I had been consistently writing revolutionary poems dated since the coup. From those, I published an e-book called Revolutionary Mindat in September. It sold quite well—each e-book was 2,000 kyats, and I was able to donate 1.5 million kyats to CDF-Mindat. The next year, I released another e-book, 32 Kotha.

Most of the poems I wrote in September were about revolutionary. Later, when I reflected, I felt some bitterness crept in. Why? Because I saw the revolution’s momentum faltering, and I noticed it among my social media friends too. I wrote a series called Momentum. Even now, as a volunteer teacher teaching Burmese, I wrote a poem about the revolutionary school that Ko Soe Ya recited on NUG’s PVTV. That poem is particularly memorable.

I started writing it inspired by our beloved comrade Che Guevara, who said, “The first duty of a revolutionary is to be educated.” In politics, the primary duty of a revolutionary is to be educated. That’s where the poem came from. It’s about how, in fighting the terrorist military, our people take on any role—logistics, support, whatever they can do, wherever they are. Everyone is a revolutionary in their own way.

While teaching, I always tell the kids, “You’re young, not yet fully educated or mature, so you don’t carry weapons. But you’re revolutionaries—revolutionary students. You attend revolutionary schools, and if you fully absorb the education you’re getting, you’re defeating the fascist/dictatorial military. They don’t want you to be educated. If you strive to become educated, you’re winning. In a revolution, you don’t need to carry a gun to win.”

Those who can carry guns will. Those who can’t will hold chalk, provide logistics, cook meals, or even gather firewood. Everyone, wherever they are, does what they can with whatever they have. That’s why I believe everyone is a revolutionary. That’s the sentiment I’ve been teaching through the revolutionary school poem.

Program Host, RAIN: Alright. We’ve learned that you’re personally teaching children at ground-level schools during this revolutionary period. In places like Chin State, where educational challenges existed even in normal times, what are the main challenges you face in these ground-level schools during the revolution? This includes military threats, lack of teaching materials and resources, concerns about teachers’ safety, or other issues. And how have you overcome these challenges?

Poet Har Shein: The primary challenge is security, particularly the threat of airstrikes. Before the town was captured, airstrikes were the main fear, along with heavy artillery. We’ve experienced two or three airstrikes, and when they happen, all the kids scatter. I’d be teaching at the whiteboard in the front, and sometimes I wouldn’t hear the airstrike warning over the children’s voices. I’d turn around and find the kids gone. When I’d go out to check, they’d be shouting, “Teacher, airstrike, airstrike!” This happened frequently.

After an airstrike—whether it hits or not—the kids are too shaken to continue lessons. Their minds are stuck on the airstrike. When our school was hit, we couldn’t do anything with the kids. No amount of coaxing or scolding worked. Despite all the drills we practiced, when an actual airstrike hit, no one could follow the training. In reality, everyone just ran chaotically to safety. That’s the main challenge.

As for teaching materials, it’s a matter of making do with what we have. If we have them, great; if not, we improvise. For things we can’t manage, we let them go. For me, teaching Burmese, the lack of materials isn’t a huge issue. Another challenge is that experienced CDM teachers aren’t returning to education. Some have gone to work in fields, others to the urban, and some abroad. Those who remain often lack enthusiasm for education. So, we rely on volunteers. As Burmese language focus, we manage, but some schools run entirely on volunteers, which creates significant difficulties.

The toughest part is teaching the youngest kids, like Grade 1 and Kindergarten. Some volunteer teachers can’t even write basic letters correctly—like confusing the letter “wahlung” with “o” or “zero.” Lower grades desperately need teaching aids/materials. Additionally, parents of slightly older kids don’t want to keep them in school. They’d rather take them to work in fields, orchards, or send them abroad. By Grade 9 or 10, parents often pull their kids out of school.

Even if students complete Grade 12, there’s no higher education available at the state level. Wealthier families send their kids to nearby places like Mizoram or New Delhi, as Chin State isn’t developed enough. Financially, in this impoverished mountainous region, parents don’t see value in investing in education, which feels uncertain. For them, working an elephant farm for three years can earn 10 million kyats, which makes more economic sense. With high commodity prices, even basic food like meat or fish is unaffordable for average families.

The main challenges are parents’ reluctance, the absence of experienced teachers in education, airstrike threats, and insufficient teaching materials. For airstrikes, there’s nothing we can do. For parents, we need to convince them and spark students’ interest in education. We must set clear goals—where will universities be established after Grade 12? Can students attend them? We can’t provide full guarantees ourselves. For quality higher education, departments need to strategize, plan, and implement on the ground. We urgently need to give the public assurances to make this work. That’s how I see it.

Program Host, RAIN: During the revolution, young people are being forcibly conscripted into military service, impacting their education. How do you think this affects Myanmar’s long-term development? What policies or priorities would you recommend to address this and build the future of education in Myanmar?

Poet Har Shine: In every region, in every school, we want all children of school-going age to be in classrooms, learning. The teachers who educate them, in this modern era, are not just sacrificing for the students; they themselves are facing dangers and challenges while passing down the best of what they have to the children. If we fail to ensure that young people who should be in school are in classrooms, the next generation—at least one generation—will fall behind.

We want many people to understand this. A generational gap has already formed, a significant disconnection. When we talk about development lagging behind, even now, the Chin Hills, which are already behind, will fall even further back. For individuals to become capable human beings, if children don’t reach the classroom, then in the future, are we going to place the responsibility of the entire Chin Hills—or, speaking broadly, the entire nation of Myanmar—on the shoulders of uneducated children? That’s the question I want to raise.

The education I’m talking about isn’t just classroom learning. It’s about being able to reason, distinguish good from bad, and differentiate between justice and injustice. As the saying goes, “Even fermenting fish paste requires a teacher’s guidance to get it right.” We want every school-age youth in classrooms. Now that the fighting in Mindat is over and we’ve retaken the town, instead of mandatory military service, we want every school-age child and youth in classrooms. That’s what we desire even more—a system where attending school is mandatory.

For this, we are laying the foundation and investing. Investing in education never results in a loss. We want to ensure children are in classrooms. If we aim to move toward a better system than what we see now, we can only progress by putting children in classrooms. That’s what I want to say.

Program Host, RAIN: Alright. The next question is about the significant role of youth and women in this revolutionary period. We’ve seen their involvement in various sectors. As a young person yourself, how do you assess the leadership and participation of youth and women? How do their roles in politics, military, education, or social sectors impact our country’s future development?

Poet Har Shine: The main leaders in this revolution are the youth and women. I don’t feel comfortable separating youth and women in this discussion because, in my view, gender discriminations belong to outdated historical concepts that should be left behind. We see women playing a significant role in the revolution. While older generations are involved, if we look at leadership percentages, women are notably underrepresented. In military matters, female leaders are very rare. Some might see this as a weakness, but women are never inferior. In some areas, they are even more capable and resilient than men.

Let me share something I remember. Many young Chin women were arrested for providing logistical support in Kalay. The look in their eyes—I can’t forget it until now. Some young men would break under interrogation, but these young women stood firm, fearless, with sharp, brave gazes. In Chin State, in groups like CNO/CNDF, we have figures like Oliver—smart, courageous, active, sharp, and strong. Look at Ram Ring—she’s outstanding. Are women inferior? Not at all. We men need to be bold enough to give them equal space. If we’re afraid women will surpass us, we’ll always be stuck in fear. Be courageous and give them space. They can do more than we can in some areas. Women often have sharper insight and are more meticulous in their work. Their strengths must be utilized effectively in the revolution.

We need to place the future of our nation, our generations, in the hands of all youth—boldly and fearlessly. But those who take on these roles must be honest. Whether it’s young people or elders leading, dishonesty will never lead to a successful political movement.

Program Host, RAIN: Thank you. In Myanmar’s Spring Revolution, there’s debate about how neighbouring countries approach it. What’s your view on the current policies and actions of countries like China, India, and Thailand? Which neighbouring country’s response do you think is most beneficial for Myanmar’s revolution?

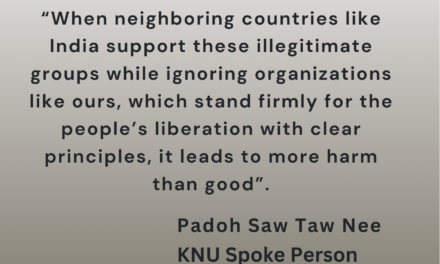

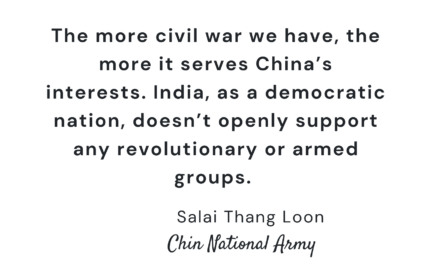

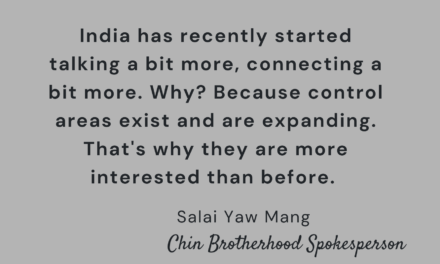

Poet Har Shine: Every nation and people prioritize their own interests. In World War I and II, every country involved acted for its own benefit. Even neutral countries act based on their interests. In the Spring Revolution, China, India, and Thailand are looking at their own interests. China focuses on Myanmar’s valuable timber and gems, assessing whether the post-revolution government will benefit them. Since they see little gain, they align with the military, as it serves their interests. India, similarly, as a major power, prioritizes its own benefits. Thailand’s people support our revolution, but their government does not. Why? If the revolution succeeds and Myanmar prospers with its resources, it could surpass Thailand in a decade under a good government. Thailand doesn’t want that, so they don’t support us. Their interests dictate their stance, and we’ve had to rely on our own efforts to reap the fruits of this revolution.

We must keep striving until we reach our goal. Diplomatically, we need to work with neighbouring countries to balance mutual interests. Revolutionary groups acting as governments must function like actual governments in their controlled areas. If the NUG acts like a true government, neighbouring countries will start to accept us. For our revolution, the most valuable contributors aren’t neighbouring countries but the people (Myanmar Citizen) themselves. Revolutionary groups must always remember this. If they dismiss the people as insignificant, the revolution will collapse overnight, despite all our efforts.

Program Host, RAIN**: Thank you. We’ve seen divisions among revolutionary forces due to differing political stances. What’s your view on this, and what should be avoided or pursued to achieve unity? What changes does the NUG, as the revolutionary government, need to make?

Poet Har Shine**: To resolve differences among revolutionary groups, we must rely on the people’s strength. Divisions arise when groups fail to listen to the people’s voices. The people will express their struggles, and we must listen. In the case of the Chin issue, the main thing is to listen to the voice of the public.

What to avoid? Ego and self-interest. What to pursue? Listening to the people’s voices. For the NUG, it needs to transition from a “virtual government” to a “grounded government.” The NUG must effectively manage its core principles (the “three Ps”). If they can do that, they’ll succeed. Even in challenging areas like central Myanmar, the NUG faces difficulties, so revolutionary groups should learn from each other’s strengths. No group is perfect, but by adopting each other’s good practices, we can bring comfort to the people.

Program Host, RAIN: Thank you so much for taking the precious time to answer our questions today.

Poet Har Shine: Thank you.

Note: This translated text represents our effort to help international observers of Myanmar affairs gain a more accurate understanding of the actual situation in Myanmar. If there are any shortcomings in the translation, we respectfully request that you consider the original Burmese meaning as the authoritative version.